In Bihar’s overlooked Supaul district, Saroj Kumari is tackling malnutrition at its root – using trust, creativity, and lived presence. This isn’t just public health; it’s quiet resistance where it matters most.

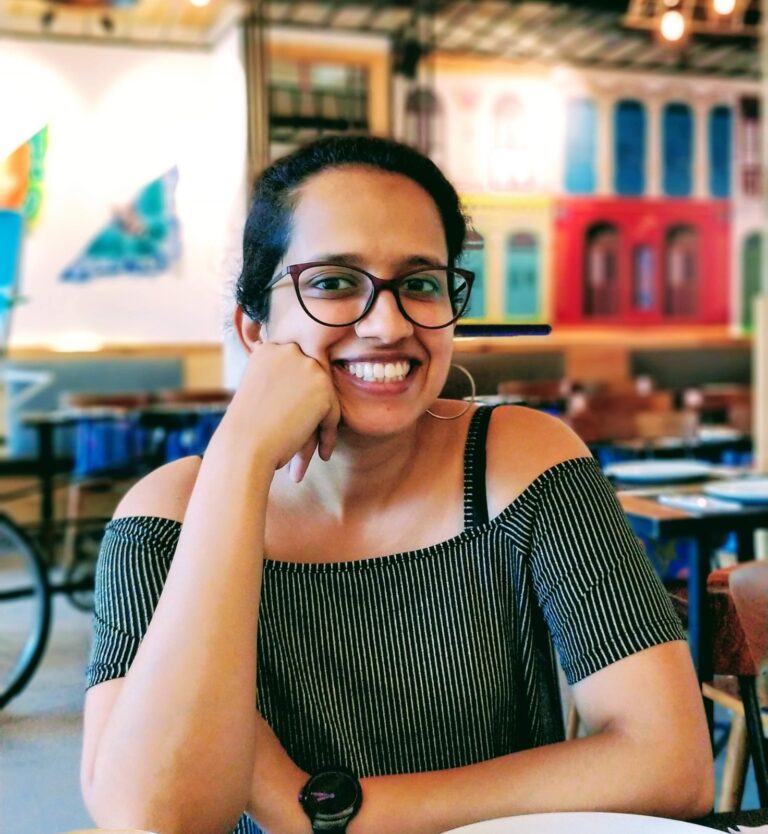

Saroj Kumari is the founder of ZealGrit Social Welfare Foundation, a grassroots organisation combating malnutrition in rural Bihar. After studying global public health and policy on a Chevening scholarship and working across sectors — from bureaucracy to nonprofits — Saroj returned to India with a clear purpose: to bring change where few were looking. In this conversation with Devrupa Rakshit, she speaks about what drew her to nutrition, the life-cycle approach her organization follows, and why she chose to start in Supaul, a district rarely even mentioned in policy conversations.

Tell me about your organization, and what drew you to the work you’re doing now.

At Zealgrit, we tackle malnutrition in rural India using a life-cycle approach. We started in Supaul, Bihar — a flood-prone district that’s largely neglected in development efforts. My background is in public health and nutrition, and I’ve always been fascinated by how what we eat affects our bodies. The first thousand days of life and adolescence are crucial phases of growth, so that’s where we focus.

We work directly within communities. We’ve adopted one panchayat with 12 anganwadi centers and identified pregnant and lactating women through both anganwadi workers and our own presence on the ground. We offer monthly one-on-one support — explaining baby development, nutrition, antenatal care, and family involvement. It’s not just information-sharing; we cook with them, feed babies together, and build trust so mothers feel comfortable asking questions.

As part of our adolescent health project, we’ve developed 20 activity-led sessions across six schools, reaching over 1,200 students so far. These aren’t just lectures — they’re immersive and creative. One example is a custom-designed snake and ladder game that sparks discussions around topics like UTIs. Each session connects to an aspect of adolescent health and well-being, directly or indirectly.

We also offer capacity-building for frontline workers. These aren’t pre-designed trainings — we respond to gaps we observe in real time.

What inspired you to work in this specific sector?

My own upbringing had a big influence. My father was in the Navy, and our household was disciplined — no processed foods, lots of home-cooked meals, daily physical activity. That sparked my interest in nutrition. But I knew clinical work wasn’t for me. I didn’t want to write diet charts forever. In college, I discovered public health, which allowed me to work at the population level, beyond hospitals and labs.

After studying at Queen Mary University of London, I returned to India and decided to start something grounded. I didn’t want to sit behind a laptop working on policy; I wanted to be where the problems actually are. Supaul is my husband’s hometown. When I visited, I saw what it meant to be truly underserved — girls missing school due to periods, babies born without medical help, families sleeping hungry. I couldn’t unsee it. So, I stayed.

What gap are you filling, and why does that feel urgent?

We’re simply showing up for people no one else thinks about. Supaul isn’t developed or “aspirational” — even MPs have said this in Parliament. Most organizations don’t come here because the roads are bad and logistics are tough. But that’s why I chose it. Everyone wants ease; I chose the challenge.

We work with Dalits, Muslim minorities, and Musahar communities — historically dehumanized and still discriminated against. Before you can talk about behavior change, you need to bridge massive information gaps. That’s urgent because almost every second child is malnourished, and nearly every mother is anemic, which are both really problematic.

What’s one big challenge you’ve faced so far?

Interestingly, opening a bank account was a massive challenge. It took six months. Government banks didn’t know how to support a non-profit. Private banks weren’t much better.

Another challenge is the way some men respond to women in leadership. They don’t know how to deal with women who assert themselves. Many people didn’t know how to interact with a woman asserting herself in these spaces. They’d ignore me, question my presence, or act like I didn’t belong. There’s also resistance from mid-level government staff — not frontline workers or top officials, but the ones in between. They’re suspicious of us, maybe worried we’ll uncover something. But we’re not grassroots reporters, we are grassroots practitioners.

Surprisingly, most of the pushback often came from the more “educated” crowd — extended family, acquaintances, friends. But on the ground, in the communities and schools, the response was warm and affirming.

What kind of change are you hoping to create?

If no child under five and no adolescent ever suffered from malnutrition, that would be the dream. More so, because malnutrition is about lost opportunities, too: kids dropping out, girls getting trapped in early pregnancies, stunted brain development leading to lifelong economic disadvantages.

Every mother should be able to access health and nutrition services without fear or bribes. These services are technically free, but often, not in practice.

What’s next for you?

We’re building proof-of-concept models that can show deep, sustained impact — not vanity metrics. Because poverty is at the root of malnutrition, we’re creating livelihood opportunities for women. Not just jobs, but dignified work that gives them purchasing power and autonomy.

Even if we work with just one district or a few panchayats for years, that’s fine. Impact takes time. This isn’t a “we reached 20,000 people” kind of story. We don’t want surface-level scale — we want meaningful change.